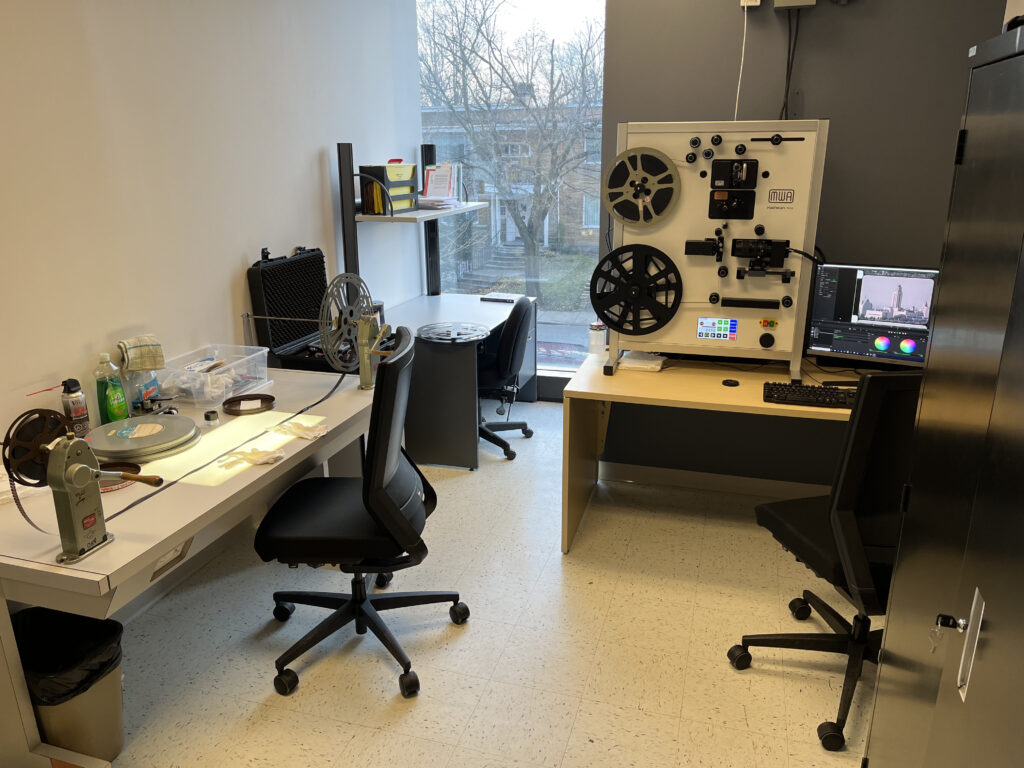

This new equipment, installed in the Laboratoire CinéMédias, is the latest in technology and will make it possible to restore films for research, preservation and creation purposes.

Olivier Du Ruisseau

The Laboratoire CinéMédias recently acquired a film digitiser equipped with the latest technology thanks to a grant from the John R. Evans Leaders Fund of the Canadian Foundation for Innovation (CFI). This new equipment will support various projects at the laboratory and at the Canada Research Chair in Film and Media Studies. It will also make it possible to digitise the university’s vast 16mm film collection and make it accessible online.

“This acquisition puts the laboratory in the front ranks of everything concerning our cinematic heritage,” remarks Louis Pelletier, a researcher at the Laboratoire CinéMédias and a specialist in cinema’s technical history. The digitiser will not only be useful to research professionals, but will also be made available to students under a microprogram in film archiving and heritage which should see come into existence in the next few years.

For the moment, this prized tool – only a handful exist in Canada – has already proved its worth. The first films from the Université de Montréal collection have already been digitised, and hundreds more will follow. Some may be made available in open access on Cadavre Exquis, a platform associated with the digital film magazine Hors Champ which will be launched in the coming months and which will be headed by André Habib, a member of cinEXmedia.

Professor Habib was, moreover, one of the two researchers who submitted the funding request to the CFI, along with Santiago Hidalgo and André Gaudreault (main researcher), both codirectors of the Laboratoire Cinémédias.

“Redefining Cinema”

These films come from the audiovisual collection of the university library, the university’s archives or its academic departments. The collection as a whole contains a broad range of objects, some of which date from the early twentieth century, including scientific and educational films, student films and promotional material for the university.

“It is important to redefine the cinema we wish to valorise, especially in Quebec, where fiction film arrived later,” remarks Pelletier. “These films could be interesting documents from a research perspective, but also fine works of art.”

As an example, Pelletier cites the “microcinematography” of Albert Caron, known as Père Venance. “This Quebec scientist filmed micro-organisms from the 1930s to the 1950s using a 16mm camera combined with a microscope. His films, which today belong to the university, personify the history of scientific research in Quebec. The recount how people adopted new technologies for teaching, in addition to having great potential for re-use by artists.”

Some films in the collection, and particularly promotional films, show public figures in Quebec in their youth, such as the filmmaker Denys Arcand and the animator Christine Charette. Filmmaker Jean-Marc Vallée, who studied film studies at the Université de Montréal in the 1990s, signs on as director of photography for a student production.

Louis Pelletier is particularly proud of the restoration of a film shot in the Cree community of Chisasibi in the early 1950s. “I had it digitised, telling myself that it was not only a beautiful film, but that it must have historic value because of the rarity of films shot in the region, especially back then. In the end it found an audience on YouTube: more than 5,000 people have watched it. A television production company even contacted me to use it in a program on the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network. This illustrates the extent to which digitising archival films can be useful.”

Laser Technology

The Université de Montréal’s digitiser is almost comparable to the highest-quality equipment in the field, such as that found at the National Film Board of Canada. “To avoid catching on the film and risking damage to it, the device uses a laser beam to locate each perforation and give the command to capture each image,” Pelletier explains. “It is ideal for archival films, which are often more fragile.”

The device is not adapted for 35mm film, but it can digitise 16mm, Super 16, Super 8 and 9.5mm film. “No matter what the format, the digitising is of very high quality,” Pelletier continues. “Most of the university’s films are in 16mm, so the digitiser is entirely appropriate for the use to which we are putting it.”

The use of digital equipment to restore films can, in certain cases, also improve the viewer’s experience, Pelletier concludes. “I’m a purist: I think we should continue to project films on celluloid, but sometimes it can be useful to digitise films to edit them and correct colour degradation, for example. It also makes it possible to make films accessible to the greatest number of people, and that is what truly counts with our collection.”