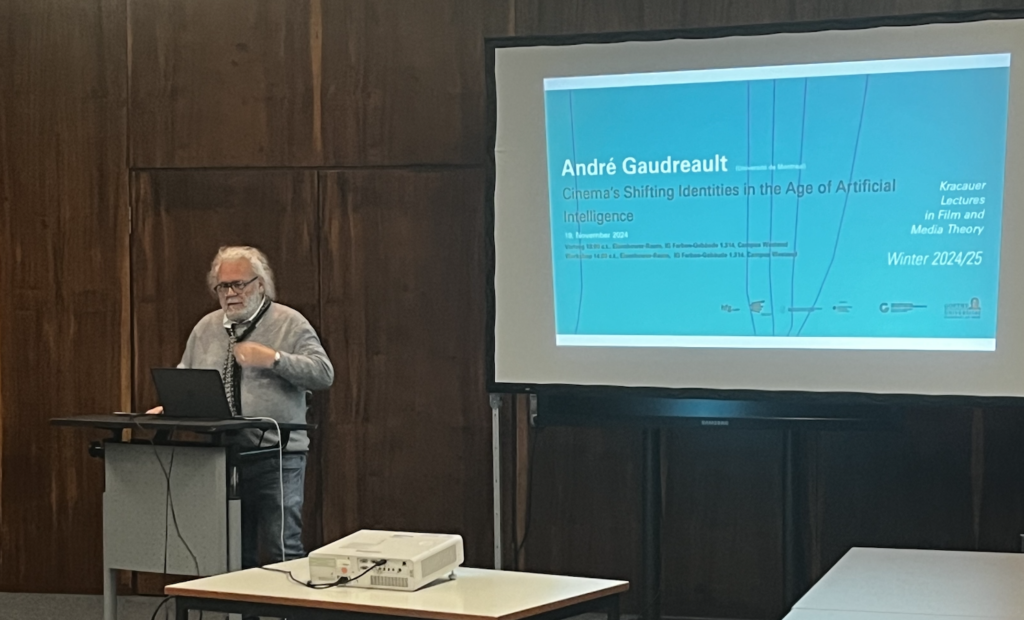

On 19 November 2024, André Gaudreault gave a lecture in Frankfurt on the upheavals caused by the advent of artificial intelligence in film production and research.

William Pedneault-Pouliot

The Kracauer Lectures, organized each semester since 2011 by the Institut für Theater, Film und Medienwissenschaft (Institute for Theatre, Film and Media Culture) at Goethe-Universität in Frankfurt, Germany, have as their objective to “present innovative contemporary scholarship on film and media from the fields of film and media studies, art history, cultural studies and aesthetic philosophy”.

Each lecture is preceded by a workshop open to students, giving them an opportunity to exchange ideas with a guest professor on a given topic. On 19 November last, students were able to speak with André Gaudreault, founding member of Laboratoire CinéMédias, on the topic of cinema’s identity and how it has been taught as a discipline since the upheavals caused by the advent of the digital.

Among other topics, Gaudreault’s lecture enabled him to address issues around the future of cinema studies, in a world in which the “media” and “audiovisual content” have taken on increasing importance in the public sphere at the expense of a more traditional view of “cinema”, along with recent changes in the names and orientations of university departments devoted to these disciplines.

Cinema’s Identity in the Face of the “Great Upheaval” of Artificial Intelligence

“Will the arrival of artificial intelligence fundamentally transform cinema? And will it affect our conception of cinema?” These were the two questions with which Gaudreault began his lecture, which provided several avenues for approaching the “great upheaval” brought about by AI.

According to Gaudreault, AI will undeniably lead to “the replacement of existing practices or crafts by others” while “obliging everyone to rework every facet of creation and production at a speed and on a scale never before seen in the history of humanity”. And so we must recognize that “AI now exists, and we must keep it in check”.

But will this lead to the end of cinema as we know it? “With the advent of the digital, cinema was toppled from its pedestal”, Gaudreault remarks. “It is now on the same level as other media, and not above them”. Yet the advent of AI, for Gaudreault, will not lead to the “death of cinema”. On the contrary, we have witnessed instead its “tenacity”, he continues. AI could thus bring about “CinemAI” or the “cyborg film”, meaning new methods of film production.

André Gaudreault has explored these issues by drawing on the concepts “cultural series” and “the double birth of media” which he has developed over the past several years with the professor Philippe Marion.

He also unveiled the initial conclusions of the project DÉMARRER (“start up”), funded by the Bureau recherche-développement-valorisation (BRDV) at the Université de Montréal, a project which examines the “industrial, creative and social impact of artificial intelligence systems on audiovisual production”. This new endeavour includes a research-creation component, carried out with in collaboration with the artist Alain Omer Duranceau. Several of his experiments with tools associated with artificial intelligence, including the previously unseen short film Neither Man Nor Movie, created entirely with text-to-video and text-to-music tools, were shown to those attending Gaudreault’s lecture.

Artificial Intelligence as a New Topic of Research

We should point out that André Gaudreault’s lecture did not attempt to provide definitive answers to these questions, which all in all have been posed quite recently. Instead, his lecture set out issues that have occupied him and his collaborators over the past year. As he related to us in an interview on the sidelines of the event, the issues he raised arose alongside the advent of AI as a topic of research at Laboratoire CinéMédias.

“The biggest event was the arrival of Sora”, he says. This new text-to-video tool from the company OpenAI appeared in February 2024. It was at this moment that he realized the need to study artificial intelligence in his research and in his “Cinema and Digital Culture” seminar, which he was offering at the time at the Université de Montréal.

Things followed on from one another rapidly after Sora’s appearance, Gaudreault explains. In March 2024 he and the post-doctoral researcher Marie-Odile Demay applied for a grant for the DÉMARRER project, which they received a few months later. At the same time, he concluded his “Cinema and Digital Culture” seminar with a class devoted entirely to AI – a sign that a major transformation had taken place in a very short period of time.

He had already been exploring the broader topic of the “digital revolution” for decades, and points out, moreover, that he wanted to “study the connections that may exist between the emergence of AI and the previous digital revolution”. “In each case”, he explains, “I had the intuition that we were in the field of ‘advanced information technology’. Gradually, I came to realize that AI is necessarily the future of cinema. Unfortunately, perhaps, but that’s life. And that is why I became interested in AI from the perspective of media identity”.

In Gaudreault’s view, the current craze for AI shows no sign, moreover, of running out of steam. “It’s going to continue to advance”, he says enthusiastically. And so today he heads up several research projects connected to AI which will soon come into being, particularly as part of the Programme de recherche sur l’archéologie et la généalogie de montage/editing (PRAGM/e) and of the Groupe de recherche sur l’avénement et la formation des identités médiatiques (GRAFIM).

André Gaudreault’s lecture on 19 November at Goethe-Universität was clearly a summing up of an initial year of intensive thought by him and his collaborators on the advent of artificial intelligence. More than that, it was the point of departure for deeper research and an invitation to think collectively about the various changes wrought by this new reality.